MFA Blog

A Community Suffering in Silence: Infertility and Arab-Americans

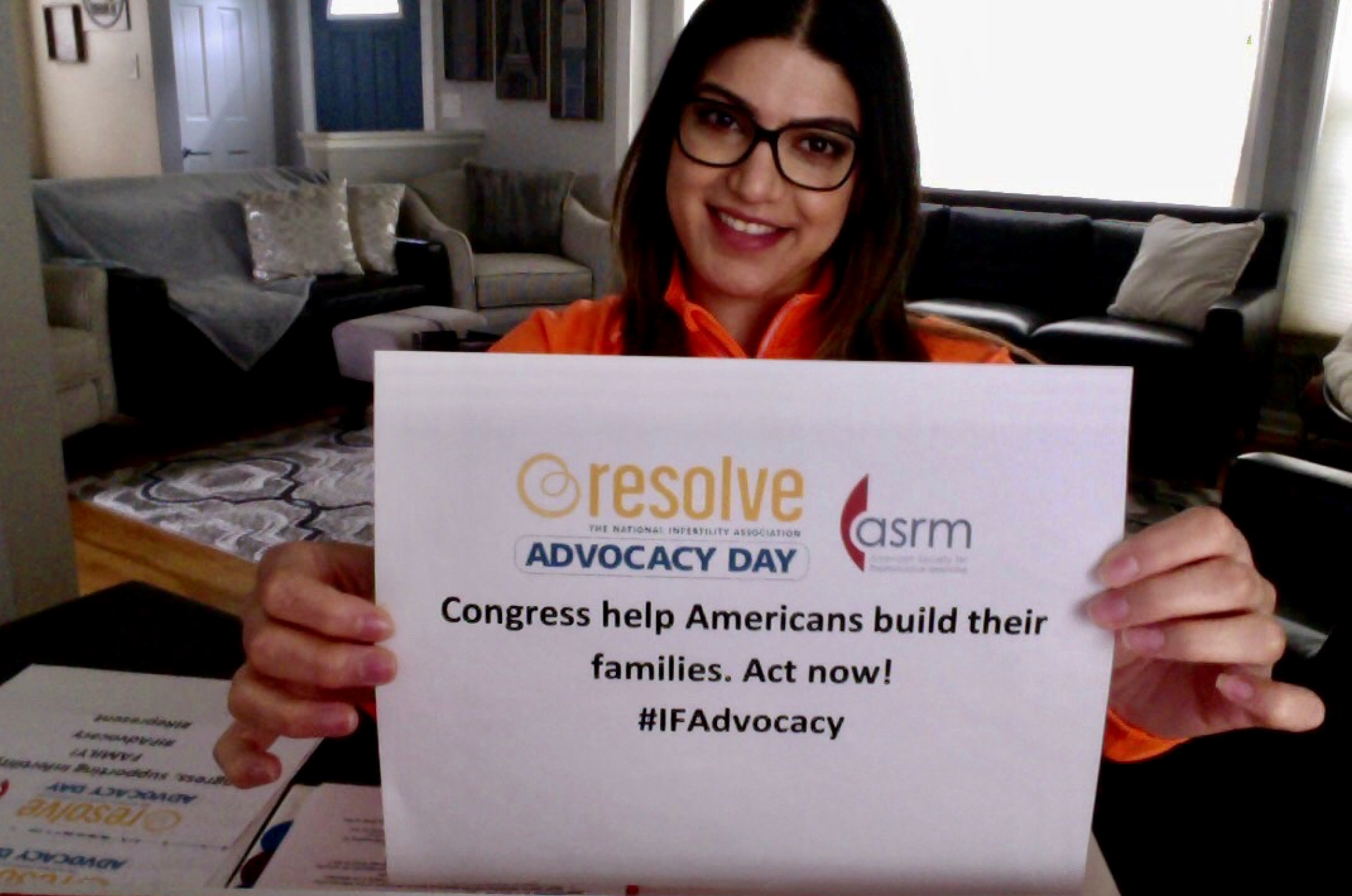

Layelle Beydoun was born and raised in the tightly knit Arab-American community in Dearborn, Michigan. (It is the largest of its kind in the United States with an estimated population of over 404,000). Soon after she and her husband were married, they discovered that conceiving wouldn’t come easy and that they would become infertility patients. The couple have been through countless surgeries and IVF cycles, so far to no avail. Through her rollercoaster fertility struggles, Mrs. Beydoun has become an advocate with RESOLVE: The National Infertility Association, participating not only in two national advocacy days and raising funds and awareness through Detroit’s Walk of Hope but also the recent Michigan Infertility Advocacy Day with MFA. She spoke with the MFA’s Ginanne Brownell and Nadia Shebli—who also comes from the same community— about her own struggles and why it is important that infertility be more openly discussed in the Arab-American community. EXCERPTS:

Brownell: Did you have any inkling that you would have infertility?

Beydoun: No. Growing up I had a very healthy lifestyle and had no major medical issues that would have indicated that I had an issue with my reproductive health. Still, I was diagnosed with having both a low anti-mullerian hormone (AMH) and a high follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), which meant I have diminished ovarian reserve (DOR) and I’m at a higher risk of premature ovarian failure (POF). When I asked why my biological clock was ticking much faster than normal, I was told, “You were just born with it.” There was nothing I could have done to prevent or cure this type of diagnosis which is chalked up to be unexplained infertility. Unfortunately, growing up I never had a pap smear or my blood drawn to test my fertility hormone levels and was actually discouraged from getting them since I was not sexually active. Had I been aware of my fertility health at an earlier age, I could have been proactive and used the opportunity to freeze my eggs while my hormone levels were still at an optimal number. This would have saved me so much time, money, and heartache but, fertility and infertility is not commonly discussed in the Arab American Community and in school our sex education classes teach us how not to get pregnant and fail to teach us how to get pregnant.

Brownell: Did you feel like you could tell anyone aside from your husband?

My husband and I are very fortunate to come from supportive and loving families. As soon as we heard about our infertility, we told our immediate family members so that they were aware of the struggle and challenge that we would have to go through to start a family. I didn’t start opening up about my infertility to others until almost three years after my diagnosis and treatments. The courage to talk about it came from infertility support groups outside my community and the national nonprofit organization group, RESOLVE. Although I’ve been an infertility patient for five years now, it still doesn’t stop other family members, friends, and acquaintances in the Arab-American community I live in from asking when I’m going to have kids if I have any yet, and what am I waiting for. When you live in a community that is not educated on the topic, their questions, concerns, and comments tend to be very insensitive even though that may not be the intention. It still discourages infertility patients, like me, from talking about our situation, which results in a community that suffers in silence.

Shebli: How do you think that connects to our community, this idea that no one discusses it?

Well, for as long as I can remember, no one that I knew in the Arab- American community talked about infertility and that’s because there’s a huge stigma surrounding the topic. I sometimes think that Arab Americans tend to feel a certain level of shame when they can’t conceive right away because our community still has an old-fashioned idea of how men, women, and couples should live their lives, and infertility goes against that image. Arab Americans have evolved in many ways but have not fully grasped the thought of how different and unique each family looks like nowadays. Whether it’s the blending of two families from a divorce, infertility, adoption, or interracial marriage, these examples are not usually expressed to be the normal idea of what an Arab-American family looks like even though it’s becoming more common.

Brownell: Why do you think that is?

The discussions we are having about infertility are very much outdated if we’re having them at all. Since infertility is such a taboo topic, our community has not had the opportunity to truly educate themselves on the actual issue. When infertility is brought up, too often I hear Arab- Americans more concerned with how it relates to their culture, religion, and reputation rather than it being an actual medical disease. With that being said, it’s hard to talk about something you feel you’re going to be prejudged about on something you have no control over. And how can we properly guide our future generations who may experience infertility with these uneducated ideas of what it is? Infertility is not a social status, it’s a disease.

Brownell: How do you go about changing the narrative?

Changing the infertility conversation. Having sex education classes also teaches how to start a family. Raising awareness in our community with the support of Arab-American medical professionals, political leaders, and educators. Forming a public infertility walk-in Dearborn where Arab- Americans come together to show their support and unity on the issue. Developing a support group that allows infertility patients to participate that makes them feel safe and also secures their privacy. Overall, just encourage the community to start talking about what obstacles infertility patients have to face in the state of Michigan to build their families.

Shebli: I grew up in a family of nurses yet I still feel like I don’t hear that much about infertility.

And that’s a part of a reason why I advocate and volunteer my hours in support groups and non-profit organizations: to raise awareness. I attend infertility support groups not only for myself but, to learn about other people's situations and further educate myself on the different experiences everyone has from a medical and social aspect. It’s important to continue the conversation because it may be a neglected topic now in our community but I want more for our future generations. Infertility might be an issue for my niece, or for my future daughter or son, or for my male and female cousins, friends or neighbors. I just don't want them to go through what I've gone through.

Shebli: Dearborn, of course, plays a huge role in the history of surrogacy, not just in Michigan but globally. Had you known that before?

No, and it was huge when I found that out during Michigan Infertility Advocacy day. It just blew my mind, especially because Michigan has had a bad grade for infertility. In 2020, Michigan was a grade D. This year it’s moved up to grade C. So it's definitely improving but, for the longest time, I think there was a lot of neglect when it came to talking about infertility in the state of Michigan.